|

| My bouquet of GRANDchildren. |

Friday, December 30, 2011

Welcoming 2012

Wednesday, December 21, 2011

Seizing the Moments

|

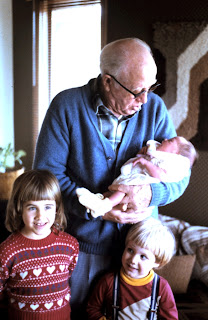

| Me and my cousins, 1955. That's me sucking my thumb. |

My concern about time-passing started a few years ago when I realized I didn’t remember my 30's. An entire decade was a blur. Why? Because the years were consumed with the logistics of being married, working, and raising three kids. My days were completely filled with have-to-dos and should-dos and love-to-dos. When I looked to the left then looked to the right, ten years had passed. Whoosh!

The prime years of my life a blur? That made me incredibly sad. But recognizing this made me stop a moment to think about the happy moments in my life that I did remember vividly. Chaotic Christmases with extended family, the abundance of cookies and laughter filling us up. The family vacations where I packed a Goody-Bag full of small surprises to be doled out to wiggly children when the miles seemed to go on forever. Or waiting backstage for my entrance in a community theatre production of “My Fair Lady”, looking up into the dark recesses of the ceiling where catwalks, lights, and scenery lay waiting, thinking about the joy I got from being on stage. These snippets of my life still make me smile and feel warm inside. But they were snippets that couldn’t be retrieved because life has gone on.

In hindsight I recognized how special these times were--but did I know it at the time? Did I stop and think, I need to appreciate this moment because it’s precious?

In hindsight I recognized how special these times were--but did I know it at the time? Did I stop and think, I need to appreciate this moment because it’s precious?To pause. That’s the key. To pause and relish it all.

This attempt to appreciate the moment has also made me more defensive of my time. Recently I've dropped two big, weekly obligations that I was involved in for years because I realized where I wanted to be was home. It was a been-there-done-that realization that has given me the gift of time. Free time. When we're younger we feel an obligation to DO. But that's fading for me. I'm content to HAVE DONE things, and move forward with fewer HAVE-TO-DO burdens.

This attempt to appreciate the moment has also made me more defensive of my time. Recently I've dropped two big, weekly obligations that I was involved in for years because I realized where I wanted to be was home. It was a been-there-done-that realization that has given me the gift of time. Free time. When we're younger we feel an obligation to DO. But that's fading for me. I'm content to HAVE DONE things, and move forward with fewer HAVE-TO-DO burdens.And so dear readers, start giving yourself the gift of NOW. Now. Amid the busyness of life find peace and joy in one fine moment. And then, another. And another. For God is good, and life is a gift to be cherished.

Friday, November 18, 2011

The Resurgence of the Fan

|

| Nancy with parasol at Colosseum |

|

| Woman with Parasol by Renoir |

It made me wonder why we've abandoned the parasol and fan. The parasol probably went by the wayside because we now embrace having a tan. But a hundred years ago, having porcelain skin revealed breeding. Only people who worked for a living had tanned skin. So I'll surrender the parasol--even though I don't do tans either.

|

| Lady with a Fan by Aviat |

In my research, I learned there was a Language of the Fan, where women could say secret things to the men in their lives by the flip of their fan. Fanning with the right hand in front of your face meant "Follow me." Fanning with your left hand meant, "Don't flirt with that woman." Slowly fanning yourself meant, "Don't waste your time, I don't care about you." While quickly fanning yourself meant, "I love you so much."

|

| Lady with a Fan by James Tissot |

Which leads to a bigger question: did men really understand this special, intricate language? Not to disparage the other sex, but I've noticed that most men I know don't pay attention to what a woman is wearing, if their hair is worn up or down, or even if they wear glasses, much less notice whether the woman runs her fingers over the fan's ribs (meaning "I want to talk to you") or carries the fan closed with the left hand (meaning "I'm engaged.") Sorry, but it ain't going to happen.

|

| Lady with a Fan by Mary Cassatt |

Friday, November 11, 2011

Mourning Dress

The ladies who read the 19th century article titled "Mourning and Funeral Usages" posted here:

The ladies who read the 19th century article titled "Mourning and Funeral Usages" posted here:

Friday, September 23, 2011

The Inventor You Never Knew

He’s the inventor no one knows, yet the inventor of many things that are still used today—or that evolved into things we use today. Then why don’t we know him?

Because he worked behind the scenes and because he made mistakes--mistakes we can learn from today…

He was born in 1796 in New York state. As a young man he lived in the textile mill town of Lowville, New York. His family worked in the mills. The entire town depended on the mills. When the mill owner wanted to lay people off because he was losing money, Hunt convinced him it wasn’t because of the workers, but because the machines were inefficient. To fix the problem, Hunt invented a better flax spinner and the workers’ jobs were saved. Bravo. Way to go.

But then Hunt made the first of a series of mistakes. And so our lessons begin. . .

PATIENCE IS A VIRTUE: Good things come to those who wait. Throughout his life, Walter Hunt went for the quick gain rather than being patient and looking at the bigger picture. After inventing his flax spinner he went to New York City and sold the patent. He got quick money up front. But by doing so he ended his chance to reap any profits from the machine over time.

LEARN FROM YOUR MISTAKES: As an inventor, Hunt had to try and fail, try and fail many times before he finally succeeded. That succession of steps was ingrained into his work ethic. But when it came to business, Hunt tossed aside this method. He failed at not profiting from the spinner, so you would have thought he would learn from his mistake of selling the rights. Nope.

Just a year after the spinner was invented, he witnessed the death of a little girl under the wheels of a carriage. It affected him greatly (as it certainly would.) Hunt recognized the problem at hand: coachmen had hand horns to beep, but in an emergency, they had to keep both hands on the reins. So Hunt invented a foot-activated gong. Problem identified, problem solved.

But once again he sold the patent before it was manufactured.

BIG GAINS INVOLVE BIG RISKS: This was a reoccurring lesson not learned in Hunt’s life. The need to pay the bills caused him to sell now rather than wait for the possibility of a larger gain in the future. Admittedly, waiting was a risk, but history shows that in most cases, the risk paid off—for someone else.

So it went with a knife sharpener, a stove, a globe caster, fountain pens, ink stands, bottle stoppers, ice-cutters for boats, paper collars, innovations in guns, and the first sewing machine. Invent it, sell it, move on. In Hunt’s defense, he was married and had four children to support. He needed money. Now.

He tried his hand at real estate, but his mind was always working, seeing a problem and inventing an answer.

For instance, while trying to figure out how to pay a $15 debt, he was fiddling with a piece of wire—and invented the safety pin. He sold the rights. The rest is history.

|

| Sewing machine drawings |

PAPERWORK PAYS & TIMING IS EVERYTHING: Hunt invented the first sewing machine in 1833. He didn’t patent it, but sold the idea to George Arrowsmith. But then there was a recession, a cholera epidemic, and labor issues—seamstresses thought the new machine would put them out of work, so Arrowsmith also let the idea slide.

A decade later, when the world had calmed down, many inventors started expanding on Hunt’s idea. In 1846, John Greenough received the first patent for a sewing machine.

Then more inventors jumped into the game, and in 1853, Elias Howe and I.M. Singer—two men who took Hunt's idea and expanded on it—were in court, battling for the rights to this very lucrative product. Howe claimed he invented the first workable sewing machine. Singer’s defense involved showing Hunt’s original drawings, dated 1834, which proved Howe wasn't the first, Hunt was (therefore Singer shouldn't have to pay Howe anything.) In the end the courts acknowledged Hunt as the first inventor, but ruled that because Hunt never filled out the proper paperwork for the patent, Howe could have it. I’m sure Hunt kicked himself on that one. The lack of paperwork, added to inventing the right idea at the wrong time, equaled nothing. Actually, Issac Singer agreed to pay Hunt $50,000 to end the patent controversy, but Hunt died before receiving the first payment. Once again, bad timing.

KNOW YOUR STRENGTHS: Even as I reveal my frustration with Hunt’s choice to sell the rights to his inventions and not take the time and energy to manufacture them, I wonder if he was wiser than I give him credit for. Perhaps he knew his strengths—and weaknesses. He clearly was not a businessman. He was good with his hands, he had a mechanical mind, but to develop a factory to manufacture his products, to think about owning a building, hiring workers, marketing the product to the public… Did the breadth of that task overwhelm him? I can imagine him most content in his workspace, tinkering with odd parts, working alone but for the churnings of his mind.

Hmm. Perhaps I need to cut the man some slack. For as a writer I often feel overwhelmed with the new world of publishing and e-publishing and networking and websites and marketing—and just want to be left alone in my workspace, tinkering with odd characters , working alone but for the churnings of my mind.

For even though Hunt didn’t reap great monetary reward (I can feel your pain, Walter) he was highly respected. On June 8, 1859, he died of pneumonia in his workshop—working until the end. I can relate to that, for on more than one occasion, I’ve found myself at my computer through sickness and surgeries and exhaustion. I’d love for my family to find “THE END” typed on the computer when I die. Dying with your boots on isn't a bad way to go.

RESPECT AND SATISFACTION ARE WORTH MORE THAN MONEY: All this begs the question of "What is success?" Is it measured by money? Fame? Walter Hunt never earned a lot of money, but he provided for his family. He wasn't famous, but he enjoyed his work. After his death, the New York Tribune wrote this about him: "For more than forty years, he has been known (for his) experiments in the arts. Whether in mechanical movements, chemistry, electricity or metallic compositions, he was always at home: and, probably in all, he has tried more experiments than any other inventor."

Which leads to a very important life lesson: IF AT FIRST YOU DON'T SUCCEED, TRY, TRY AGAIN. Life is all about trying. And failing. And trying again. Hunt did that better than most.

Walter Hunt, inventor extraordinaire, I owe you an apology. Because hindsight is 20/20 I can look at your life and see your blunders. Yet I cringe when I think of someone in the future dissecting my life, my mistakes, and my missed opportunities. You used your gifts, which is more than a lot of people do: "From everyone who has been given much, much will be demanded; and from the one who has been entrusted with much, much more will be asked." Luke 12:48

So here it is. My apology and my kudos. You did good, Walter. I understand you better now--and I appreciate you./Nancy

Thursday, September 15, 2011

Quilts and Historical Fiction

I readily admit that “it’s the history” that draws me to historical fiction. And it’s a good thing that I love history, because writing historical fiction means that before I dress, move, or feed anyone … I have to do research. I’m never happier than when I’m in my studio surrounded by piles of “dry” (to others) history books, historical documents, sepia-toned photographs, and enlargements of historical settings (see photo at right) for my current

work-in-progress I literally end up in a “nest” surrounded by ephemera and, on occasion, patchwork.

work-in-progress I literally end up in a “nest” surrounded by ephemera and, on occasion, patchwork.Patchwork?! Yep. I'm an avid textile geek. I adore old fabric and have several running feet of antique quilt

tops and quilts stored in a walk-in-closet just off my office. In fact, one set of quilt blocks in particular played a role in my beginning the story that became my first novel back in 1995. I’d stood in the hot sun for hours waiting for an auctioneer to sell a box of rags … because among the “rags” were some diamond-shaped quilt blocks that, had they ever been finished, would have made the center of what quilt lovers call a Blazing Star or a Bethlehem Star quilt.

tops and quilts stored in a walk-in-closet just off my office. In fact, one set of quilt blocks in particular played a role in my beginning the story that became my first novel back in 1995. I’d stood in the hot sun for hours waiting for an auctioneer to sell a box of rags … because among the “rags” were some diamond-shaped quilt blocks that, had they ever been finished, would have made the center of what quilt lovers call a Blazing Star or a Bethlehem Star quilt. myself wondering about the papers used and wondering … was she upset with God when she cut up that devotional book or Sunday School manual?

myself wondering about the papers used and wondering … was she upset with God when she cut up that devotional book or Sunday School manual?

Since my books are usually set in the 19th Century on the Great Plains, I can reference quilts as bedding, room dividers, front doors and more … and I can use quilting bees as natural settings for conversation and competition among women. A courthouse steps quilt plays an important role in next year’s release with Barbour titled The Key on the Quilt.

I sometimes give a lecture called “Dress Your Beds Fashionably” that shares general guidelines for what a bed would “wear,” in a given time period, but my knowledge of quilt history helps me dress my ladies, too. The book Dating Fabrics, A color guide 1800-1960 by Eileen Jahnke Trestain includes color plates of popular fabric divided by era: Pre-1830, 1830-1860, 1860-1880, 1880-1910, and so on up through 1960. It’s a wonderful resource that helps me “see color” in my sepia-toned photograph collection.

The more I learn about antique quilts and textiles, the more I want to know. I’m fortunate to live near the International Quilt Study Center and Museum in Lincoln, Nebraska, where exhibitions never cease to inspire more questions and lead me on new quests to get to know the women behind the quilts. I never know when a new idea will spring up as I ponder patchwork.

If you’d like a copy of the hand-out I provide when I give my “Dress Your Beds Fashionably” lecture, I’d be happy to e-mail a copy. Just send your request to Stephanie@Stephaniewhitson.com, and indicate “Dress Your Beds” in the subject line.

"Life is just a patchwork quilt of births and deaths and things ... and sometimes, when you're looking for a lovely piece of red, you only find a knot of faded strings ..." May your weekend bring all kinds of lovely reds!........................Stephanie

P.S. It is nearly 1 a.m. and blogger has won for today ... I apologize for the odd font sizes and margins.

Friday, September 2, 2011

Tudor England and Sandra Byrd, author of To Die For

I've been away from the blog for a few weeks, scrambling to finish up a history course for my masters, begin a new course (they overlapped...YIKES) AND my next year's novel, attending a women's conference, and welcoming a new grand-child. This week I introduce you to my writing friend Sandra Byrd and her latest ..... while I work on a blog about KEYS .... and another about SHOES .... back soon! Steph

_________________________________

I have been drawn to Anne Boleyn since I was a girl, curled up in a beanbag chair, dog-earring books about her as I read and re-read them. My research journey took me to

Meg Wyatt, narrator of my novel, whom I came to love and admire. {I will quickly note that in my book I have switched the names of the Wyatt daughters so that the eldest is named Anne/Alice and the younger Margaret/Meg so that the story could be told without two "Annes" to confuse the reader.} My story idea was sparked by one solitary clue, an offhand comment in a Tudorplace.com.ar link that said that Anne Wyatt attended Anne Boleyn till her death, and that, at the end, Anne Boley

n had given her friend her prayer book, a very personal gift indeed, and just before her execution whispered something in her friend's ear.

I'm a lifelong lover of historical novels, especially all things English. On road trips, I was the nerdy girl in the backseat of the car reading Victoria Holt and Jean Plaidy streetlight by streetlight well into the night. I even named my daughter Elizabeth! Therefore, it's a dream come true to pen my own novels set in the Tudor court. Those reformation years were critical to refinement and revival in Christianity. Yet I found that while Anne's faith, and the faith of her friends, was well covered in nonfiction, fiction only infrequently highlighted her convicti

ons, often though not always portraying her as either vixen or victim. I wanted to add some new shading and nuance to the genre and telling it from Meg Wyatt's point of view allowed me to do that. Historian Eric Ives, Anne's principle biographer, says, "The absolute conviction which drove Anne was the importance of the Bible. For that reason, if her brand of reform needs to be given a label, that label must be 'evangelical.'"

My research led me to London, which was fantastic, and many fascinating details. I loved, for example, the Eavesdroppers, little faces carved into the high eaves of the Great Hall at Hampton Court Palace.

(Eavesdropper photo copyright Helen Newell, http://tinyurNewall, http://tinyurl.com/hcpeavesdroppers)

They looked soft and sweet. But they were there to remind courtiers that someone was always listening, there was always a secondary audience to anything said at court, and that behind a pleasant face could be a heart of malice. I think it's interesting, too, that being a servant or highborn attendant was a position of honor. Your status wasn't determined by the job or tasks assigned to you, but by the rank of the person you served. That's good for us to remember, too, as Christians.

_______________

Learn more about Sandra's books here: http://www.sandrabyrd.com or purchase her new book about Anne Boleyn, told from the point of view of Meg Wyatt, here: To Die For

Friday, August 26, 2011

A Dime by Any Other Name...

Recently, I went to a coin show with my husband and heard the most fascinating story that ties into my biographical novel Washington's Lady. It adds another layer to the respect I feel toward our first president and his wife, Martha.

When this country began as thirteen colonies, and even after we gained our independence from England, we continued to use British money. But since we were a free nation, it seemed logical that a new money system had to be created. American money. On April 2, 1792, the “Mint Act” was passed, giving the nation the go-ahead to mint its own coins. There were to be silver half dollars, quarter dollars, and half dismes—half dimes.

At that time George Washington was president and Thomas Jefferson was his secretary of state. As was usually the case with these patriots, they saw a problem and came up with a solution. For isn’t that the American way?

To make coins they needed someone to create a design—a die. So they put an ad in the paper and hired someone. Check. They needed a company to press the coins. So they put an ad in the paper and hired someone—John Harper, who had a press in the cellar of his house on the corner of Cherry & 6th Street in Philadelphia, just down the street from the construction of the new U.S. Mint building. Check check. But then came the biggest problem: you can’t make coins without precious metals. Where would they come up with those?

What follows could simply be legend, or it could be the truth. Knowing George and Martha Washington as I do, I choose truth, as the story fits with their character and continued sacrifice for their country.

|

| Mt. Vernon Plantation |

It’s fun to imagine Jefferson riding up to Mt. Vernon, knocking on the door, perhaps being greeted by Martha, home for a visit from the nation’s capital of Philadelphia. “Thomas. How nice to see you. What brings you to Mt. Vernon?”

I’d love to have seen the look on Martha’s face when Jefferson handed her the letter from her husband, indicating she should hand over some of their personal silver. It’s said they gave between $75 and $100 worth of silver to the cause of new coinage. Considering most people earned $1 a day, $100 was a large amount.

In 1792 fewer than 2000 “half-dismes” (pronounced “deems”) were cast, but it’s not known whether they were ever circulated or just given away as souveniers. There’s a notation in Jefferson’s diary for July 13, 1792: “rec’d from the mint 1500 half dimes of the new coinage.” But there’s also some evidence that Washington handed the half-dismes out to friends and dignitaries. So the mintage could have been more than 1500. Perhaps George was given some half-dismes for his own use, as a repayment toward the silver he provided. Whether circulated or not, the half-disme was the first step to the minting process that would follow in the newly formed U.S. Mint being built. The first widely-circulated American coins came out in 1796.

There’s also an unsubstantiated story that Martha’s profile was the inspiration for the woman’s head on the coin. I’m not sure what I feel about that story. Martha did not like being First Lady. She had the heart of a patriot, but she also had the heart of a woman, the heart of a wife. When George agreed to become the head of the Colonial army during the war—and ended up being away from home for eight years, she accepted their separation as a sacrifice for the good of the cause, albeit, not without a few complaints. But when the war was won and George was asked to be its first president, she rebelled and virtually said: Enough. Haven’t we given enough, George? When is it someone else’s turn?

But George was an ambitious man and had trouble saying no. He was president through two terms, and was the the only president to get 100% of the electoral votes. But Martha was a reluctant First Lady (though actually, the term hadn’t been invented yet.) She did not like being in the limelight and just wanted to be home with George in Mt. Vernon, “under our own vine and fig tree.” So for her to agree to have her likeness on a coin? I don’t think so.

Actually, Congress thought about putting George’s portrait on some coins, but he dismissed the idea as “monarchical”. Only kings did that while they were alive. So the Mint Act specified a "portrait emblematic of liberty." The woman on the half-dismes—whether Martha’s likeness or not—is representing Lady Liberty.

George Washington was in his second term of president in 1792, when he addressed Congress on November 6 about the new coins: “There has been a small beginning in the coinage of Half Dismes; the want of small coins in circulation calling the first attention to them.” It would seem by his statement that the half-disme was intended to be put in circulation.

Around its circumference the coin has the words: INDUSTRY - LIB - PAR - OF – SCIENCE. Translated, that means, "Industry and liberty on par with science". There is no mint mark, as there was only one minting place at the time: Philadelphia.

I saw one of the few remaining half-dismes at the coin show (it's said that fewer than 200 remain.) It was smaller than a modern dime, and weighed less. It could have been mine for $175,000. One half-dismes, in mint condition sold a few years ago for over $1 million. Yet to think that George and Martha and Thomas might have held that particular coin in their hands…or Benjamin, or John or Abigail… I get heady thinking of it./Nancy

Friday, August 12, 2011

Dead and Buried

For one thing, there are some pretty important people-of-history buried inside: Michelangelo, Galileo, Rossini are buried there (to name but three.) An artist, a scientist, and a composer. The years of their deaths span centuries, Michelangelo in 1564, Galileo in 1642 & 1737 (more on this later), and Rossini in 1868. Because so many famous Italians are buried here, the church has been known as the Temple of the Italian Glories, for these men certainly brought glory to their country. We still celebrate and marvel at their achievements.

|

| Michelangelo's tomb |

|

| Galileo's tomb |

The last tomb to mention... even if you don’t know Gioacchino Rossini by name, I bet you’d recognize his music. He wrote 39 operas. The "William Tell Overture" is the theme music to the 1950’s TV show, “The Lone Ranger”, and there was a Bugs Bunny cartoon featuring Rossini’s "Barber of Seville". Surely the composer would turn over in his grave. He was originally buried in Paris, but at the request of the Italian government, his remains were moved to Santa Croce in 1887—nineteen years after his death. Florence wanted to lay claim to this “Italian Mozart.”

Beyond these grand tombs (and there are many more), I was most moved by the gravestones on the floor, grave after grave that we walked upon. Most were worn from the tens of thousands who have visited the church over the centuries. I mentioned to our guide that it felt wrong walking on them, but she said that being walked on, having their graves worn by the masses, was considered part of their penance. Don’t tread on me!

The point is, the dead do tell tales. Very interesting ones./Nancy

Friday, July 29, 2011

Keeping Hope Alive

Yet even with St. Paul's being the place of Diana's wedding, the piece of history that touched me the most happened forty years earlier.

As we approached St. Paul's, our London guide stopped and had us admire the dome. It turns out the dome was a beacon of hope for Londoners during World War II.

London endured "the Blitz", a period of eight months when Hitler bombed the city with the intent of demoralizing its citizenry. It all started on September 7, 1940, at 4:00 PM. Unable to invade England, Hitler sent 348 German bombers escorted by 617 fighters to bomb London for two hours. Then, guided by the fires, another wave flew over and added more destruction.

For 57 consecutive days London was bombed. The parents of our guide (children at the time) were sent to the country, to safety.

Some of the bombs were explosive, but others were phosphorus bombs that caused fires. Hundreds of volunteers manned the roof of St. Paul's with the sole job of throwing sand or dirt on those phosphorus bombs when they landed, snuffing them out. Water would have allowed the phosphorus to spread and burn more. Each morning, as the citizens of London came out of their hiding places, they looked for the dome of St. Paul's. If it was standing, they were standing. England was still standing. Churchill made saving St. Paul a priority for the morale of England.

The worst day of bombing came on December 29, 1940. Dozens of fires were put out and a bomb that lodged in the dome fell away, damaging the Stone Gallery, but leaving the dome intact. Here's a famous photo taken by Herbert Mason, showing St. Paul's rising above the smoke.

I was inspired by the spirit of the Londoners who helped each other get through this awful time. Over 20,000 died during the raids and 1.5 million homes were damaged or destroyed. Because of their tenacity and the courage of the British armed services, Hitler's plan was curbed. He stopped the bombing in May of 1941 and turned his attention to the Russian front.

|

| American Memorial Chapel and the Roll of Honour |

I was also moved by the American Memorial Chapel in the apse of the cathedral. It honors American servicemen and women who died in World War II. It was paid for by donations from British people. There's a Roll of Honour that contains the names of more than 28,000 Americans who gave their lives in the defense of the United Kingdom in WWII. Inside its glass case are a pair of gloves. Each day a page is carefully turned so that every name is seen by the public. It takes over 14 months to go through the book--and then they start over from page one. I found this very touching, especially since my father served in the South Pacific in the Air Force for 2.5 years during the war... He's 91 now, and the sacrifice of that generation humbles me.

The Duke of Wellington is buried in St. Paul's, as is Admiral Nelson, and the architect of the church (and many London churches), Sir Christopher Wren. So it's a place of internment, of weddings, of memorials, and honor. As a newspaper said a few days after the horrible December 29 bombing: St. Paul's "symbolises the steadiness of London’s stand against the enemy: the firmness of Right against Wrong.”

Long may it stand.//Nancy

Thursday, July 21, 2011

The Trip of a Lifetime

|

| The Moser gang at Versailles |

|

| St. Peter's in Rome |

|

| Eiffel Tower in Paris |

|

| The Roman Colosseum |

We were humbled by history as we saw the tomb of St. Peter, the Roman Colosseum, the actual armor of Henry VIII, and the stunning St. Paul's Cathedral in London where I remember watching Princess Diana get married back when I was a young mother . . .

|

| On the top of the Alps in Switzerland |

|

| Marie Antoinette and her children |

Adding to my interest of her, was the revelation that this Marie Antoinette was the same girl I'd written about in my bio-novel Mozart's Sister. As a child Maria Antonia had heard the young Mozart and his sister Nannerl give a recital in her family's palace in Vienna. When five-year-old Wolfgang tripped during the concert, Maria helped him to his feet. The impulsive little Wolfgang kissed her, said he was going to marry her, and then had the gall to climb into the lap of Maria's mother, the empress. That girl was this woman...

At Versailles, as I stood with my own family beside me and looked upon this grown up Maria Antonia--Marie Antoinette--I learned of another family's trip, taken in an attempt to flee France during the chaos and danger of the French Revolution. As the masses of the suffering poor rose up against the decadence of the ruling class, Marie's world of luxury crumbled around her. So she and her husband the king fled with their three children, hoping to escape to monarchy-friendly Montmédy in northeast France. But before they could find freedom they were caught and returned to Paris. All were imprisoned, and Marie and Louis were eventually beheaded by the mobs who demanded satisfaction.

But what of the children in the painting? There is an empty cradle in the background that sorrowfully represents Marie's youngest daughter Sophie who had died during the painting of the portrait, just before her first birthday. The oldest daughter, Marie Therese, standing at her mother's right, was exiled to Austria. She married but was childless. The little boy, Louie Joseph--the heir--died of TB during the tumulutuous political times, and the baby on her mother's lap (Louie Charles) died in prison. And so the Bourbon line of France was destroyed.

Seeing this painting, hearing this story, walking beside my own husband and children, I felt compassion for this queen. This woman. This mother.

It would not be the last time I would count my blessings on this trip . . .